What Moves Gravel-Size Gypsum Crystals Around the Desert?

A massive whirlwind, known as a “gravel devil,” sweeps across the Salar de Gorbea in the Atacama Desert, Chile. These powerful vortices are strong enough to lift and transport large gypsum crystals. Image credit: Kathleen Benison.

The world’s deserts are full of mysteries. From the shifting sands of the Sahara to the shimmering salt flats of Bolivia, these arid landscapes often defy our expectations. But perhaps one of the most intriguing puzzles is the movement of large, gravel-sized gypsum crystals in some of the most desolate places on Earth. How do these fragile, blade-like crystals, some as long as a human foot, travel for miles across the desert floor, seemingly of their own accord? The answer, it turns out, is as dramatic and awe-inspiring as the desert itself.

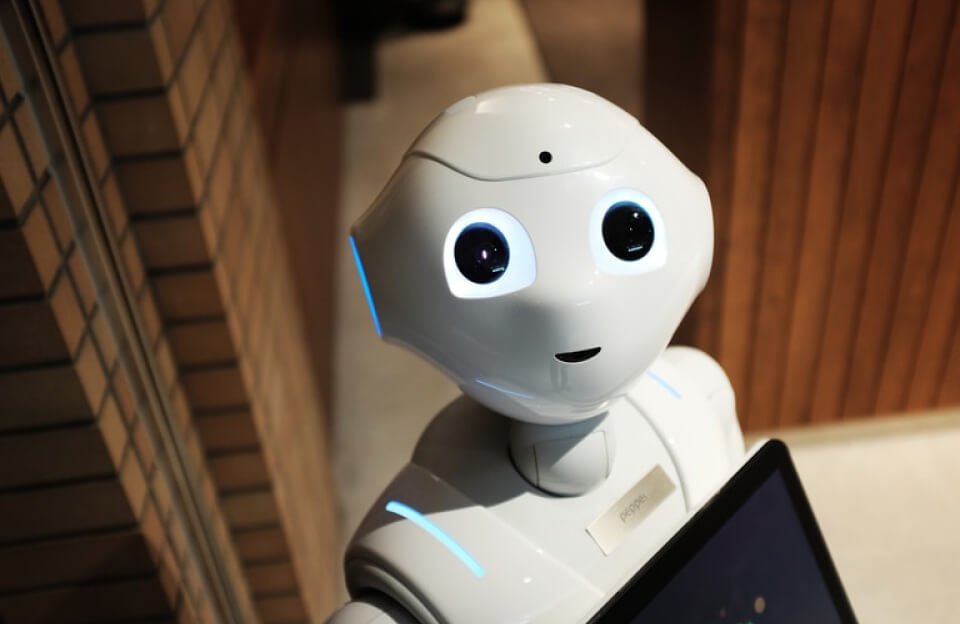

For years, scientists have been captivated by the phenomenon of rocks and crystals moving in seemingly impossible ways. The most famous example is the “sailing stones” of Death Valley’s Racetrack Playa, where boulders weighing hundreds of pounds leave long, mysterious trails in the dried mud. But in the high-altitude deserts of the Andes, a different, even more powerful force is at work, a force that can lift and carry large gypsum crystals through the air like a scene from a science fiction movie. This is the story of the “gravel devils” of the Atacama Desert, a discovery that is rewriting our understanding of what wind can do.

The Crystalline Heart of the Desert: What is Gypsum?

Selenite crystals, a variety of gypsum, forming at White Sands National Park. Image credit: National Park Service.

Before we delve into the forces that move them, let’s first understand what these remarkable crystals are. Gypsum is a soft sulfate mineral with the chemical formula CaSO₄·2H₂O, meaning it is a calcium sulfate dihydrate, with two molecules of water incorporated into its crystal structure. This water content is key to its unique properties. When heated, gypsum loses its water and turns into a fine white powder known as plaster of Paris. When water is added back to this powder, it rehydrates and hardens back into gypsum, a property that has made it a vital component in everything from construction materials like drywall to everyday products like toothpaste.

In desert environments, gypsum often forms through a process of evaporation. In the Tularosa Basin of New Mexico, home to the famous White Sands National Park, mountains rich in gypsum are slowly eroded by rain and snowmelt. This water, now carrying dissolved gypsum, flows down into the basin, which acts like a giant bathtub with no drain. The water collects at the lowest point, forming a shallow, salty lake called Lake Lucero. As the intense desert sun evaporates the water, the dissolved gypsum recrystallizes, forming beautiful, translucent crystals of selenite, a variety of gypsum. These crystals can grow to impressive sizes, with some reaching the size of bicycle tires.

The Mystery of the Moving Crystals: Enter the Gravel Devils

A powerful gravel devil churns across the Salar de Gorbea, a high-altitude salt flat in the Chilean Andes. Image credit: Kathleen Benison.

For years, the presence of large, scattered gypsum crystals in the Salar de Gorbea, a remote, high-altitude salt flat in the Atacama Desert of Chile, puzzled scientists. These crystals, some as long as 27 centimeters (10.6 inches), were found in large mounds, miles away from the acidic, salty pools where they had formed. How did they get there? The answer came in the form of a dramatic and previously undocumented weather phenomenon: the “gravel devil.”

Geologist Kathleen Benison of West Virginia University was studying the extreme environment of the Salar de Gorbea when she witnessed these incredible whirlwinds firsthand. As she described in her research, these were not ordinary dust devils. These were powerful, tornadic vortices, several kilometers high and up to 500 meters in diameter, that appeared every afternoon in the valley. She watched in amazement as these “gravel devils” lifted and transported the large gypsum crystals, scattering them across the desert landscape.

“I remember holding one of the crystals and noticing how they were all broken,” Dr. Benison told The New York Times. “I looked up, and there was one of these gravel devils.” [1]

Benison’s observations, published in the journal Geology, provided the first direct evidence of wind-driven transport of gravel-sized particles in suspension. The blade-shaped gypsum crystals showed clear signs of abrasion, indicating that they had been violently churned against each other while airborne. The gravel devils were so powerful that they could carry these crystals up to 5 kilometers from their source, depositing them in massive, 15-foot-high dunes of “gypsum crystal breccia.”

This discovery has profound implications for our understanding of wind erosion and sediment transport. Previously, it was thought that wind could only carry particles up to 2 millimeters in diameter. The gravel devils of the Atacama demonstrate that under the right conditions, wind can be a much more powerful geological force than previously imagined. The low air pressure at high altitudes, combined with the unique, elongated shape of the gypsum crystals, likely contributes to their ability to be lifted and carried by these powerful whirlwinds.

Sailing Stones: A Different Kind of Desert Movement

A sailing stone leaves a long trail on the dry lakebed of Racetrack Playa in Death Valley National Park. Image credit: National Park Foundation.

While the gravel devils of the Atacama are a dramatic example of wind-powered transport, they are not the only mysterious force moving objects in the desert. For decades, the “sailing stones” of Death Valley’s Racetrack Playa have captivated scientists and visitors alike. Here, large rocks, some weighing hundreds of pounds, slide across the flat, dry lakebed, leaving long, graceful trails in their wake. For years, the mechanism behind this movement was a complete mystery.

In 2014, a team of scientists finally solved the puzzle. They discovered that the movement of the sailing stones is not caused by powerful winds lifting them into the air, but by a delicate interplay of ice, water, and wind. After rare winter rains or snowmelt, the playa floods with a shallow layer of water. On cold nights, this water freezes into a thin sheet of “windowpane” ice. As the sun warms the ice during the day, it begins to break up into large, floating panels. Gentle winds then push these ice panels across the playa, and the panels, in turn, bulldoze the rocks in front of them. The rocks effectively “hydroplane” on the wet, slippery mud, leaving behind the characteristic trails.

“It’s a wonderful Goldilocks phenomenon,” said Richard Norris, a paleobiologist at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography and lead author of the study that solved the mystery. “Ponds like this are vanishingly rare in Death Valley, and it may be a decade between heavy enough rain or snowfall events to make a substantial pond.” [2]

The sailing stones and the gravel devils represent two fascinating, yet fundamentally different, mechanisms of desert transport. The sailing stones are a story of subtle, almost imperceptible forces working together under very specific conditions, while the gravel devils are a testament to the raw, untamed power of the wind. Both, however, remind us that the desert is a place of constant change and hidden wonders, where the seemingly impossible can and does happen.

A World of Hidden Forces

The discoveries of the gravel devils and the sailing stones are more than just solutions to geological puzzles. They are powerful reminders that our planet is a dynamic and ever-changing place, full of hidden forces and surprising phenomena. They challenge our assumptions about the limits of nature and inspire us to look closer at the world around us. From the delicate dance of ice and rock in Death Valley to the furious whirlwinds of the Atacama, the desert continues to reveal its secrets, one grain of sand, one crystal, one sailing stone at a time.

References

[1] Klein, J. (2017, April 21). What Moves Gravel-Size Gypsum Crystals Around the Desert? The New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2017/04/21/science/gravel-devils-gypsum-crystals-chile-desert.html

[2] Oskin, B. (2014, August 27). High-Tech Sleuthing Cracks Mystery of Death Valley’s Moving Rocks. Live Science. Retrieved from